130 the anti-grid

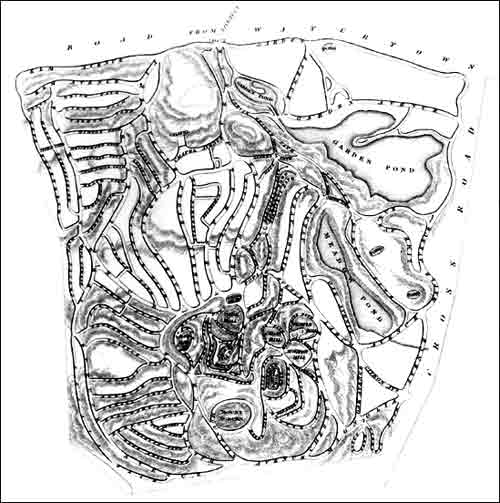

The first American alternative to the grid would not come from

architects or urban designers, but the amateur gardeners who laid out

the 'Garden of Graves', Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge,

Massachusetts (1831). Before our cities could afford parks, cemeteries

would often be a favored place for a Sunday stroll or even a picnic.

Mount Auburn, the first of America's 'Romantic era' cemeteries, with

its curving paths and informal landscaping reminiscent of an English

garden, was a revolution. Soon every city had one; among the best are

Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, Laurel Hill in Philadelphia and

Hollywood in Richmond.

Very soon after, two great popularizers would begin the job of translating the new Romantic fashion into the land of the living. In 1832, Baltimore architect Alexander Jackson Davis built what was probably America's first Gothic-style house: Glen Ellen, named for a heroine in Sir Walter Scott. He would go on to become the herald of eclecticism in America and the most fashionable domestic residential architect of his day, exhorting the rich to throw off their Greek Revival homespun to sample new domestic delights in the Gothic, in pastiches of medieval Italian architecture, even Egyptian and 'Etruscan'. Many of Davis's villas were commissioned in America's Rhineland, the Hudson Valley, which the 'Hudson Valley school' of painters had already made the New World's headquarters of Romanticism. And in many of these, the grounds would be designed in the new fashion by a local, self-taught landscape architect, Andrew Jackson Downing. Downing's A Treatise on on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, published in 1841, captured the public's imagination as no other book on the subject, before or since. In it, Americans gained their first vision of winding drives, asymmetrical layouts, and single trees strategically located as decorative focal points. With these, the great estates of the upper classes were born. Downing's opinion of cities was typical of his times; he could not imagine them as anything but commercially-dominated work camps (though some trees might help in softening and hiding bad architecture). The new landscape architecture was not about reforming the city, but escaping it. Just the same, applications in more public settings soon appeared. In 1850, Downing would be invited by Congress to re-landscape the Capitol Mall according to his theories, but died soon after in a steamboat accident, leaving the Mall with the incongruous Gothic castle of the Smithsonian (completed 1857), without the setting Downing would have given it. Downing's disciple, Frederick Law Olmsted, would get the chance to apply his principles on a grand scale in 1858 when he and Calvert Vaux won the design competition for New York's Central Park. Meanwhile, way out west in the land of Deseret, in the centre of Salt Lake City, the Mormons had started the 40-year labor of building their great eclectic Temple, set in an informal garden. In 1858, the body of President James Monroe was finally brought home from New York to Richmond. Hollywood Cemetery, with its dramatic setting over the James River, had just been completed, and a Richmond architect and the city's foundries combined to give him the finest of cast-iron Gothic tombs.

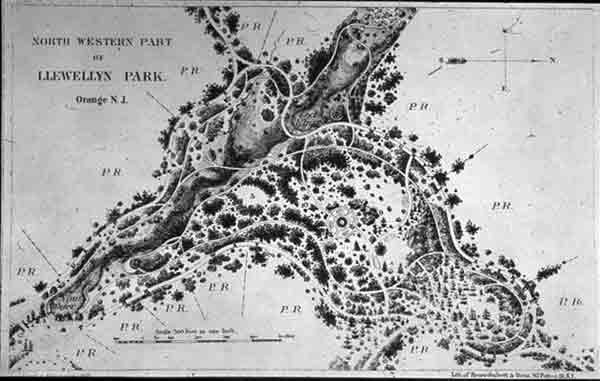

Once the green romantic visions of Downing and Davis had nested in the national psyche, industrial America and the urge to the picturesque would continue to connect and collide in surprising ways. One of their most significant collaborations was the adaptation of a British invention, the planned Romantic suburb. Llewellyn Park, in the 'Oranges' of New Jersey, was designed in 1853 by Davis, on a site bordering a railroad line to New York. Nothing so lavish or spacious had ever been seen: a central green, full one-acre lots, big homes in a melange of historical styles. Over the following decades some of America's finest architects would build here. Now, somewhat depressingly, the homeowners' association that runs Llewellyn Park boasts it was 'the first planned gated community in America'. Precocious Chicago followed Llewellyn Park only four years later with Lake Forest, a very similar scheme that would lure the cream of the city's industrial elite out of town after the Civil War and Great Fire. Less carefully planned suburbs were appearing around all the cities: in Westchester County, along Philadelphia's Main Line, and everywhere around Chicago. Where wealthy sophisticates led, the rest of the nation would not lag far behind. For those who could not afford the services of Downing and Davis, there were the proliferating manuals on gardening, the new ladies' magazines with their emphasis on the arts of the home, not forgetting that soon-to-be icon of suburbia, the lawn mower; the first practical models appeared in the 1860's, along with the first lawn-care books.

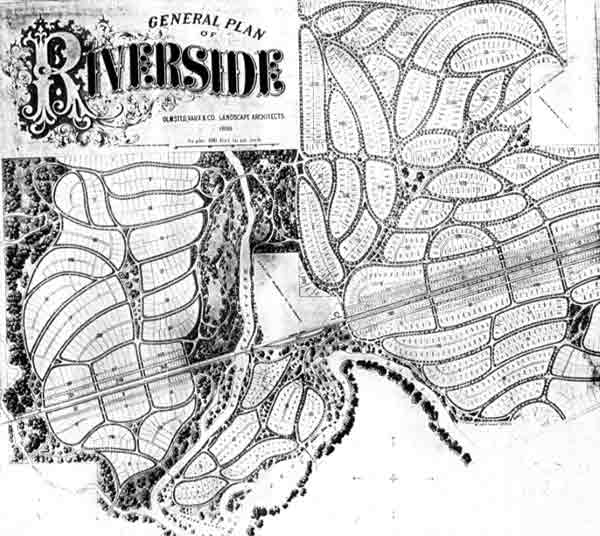

Riverside, a Chicago garden suburb designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1869. This

too was a part of America's first sprawl age, and already one

basic law of American suburban development was clear. There would be

developments of genuine distinction for the upper classes, and

mediocrity at best for everyone else.

|

|

|