034 serial vision, surprise and closure

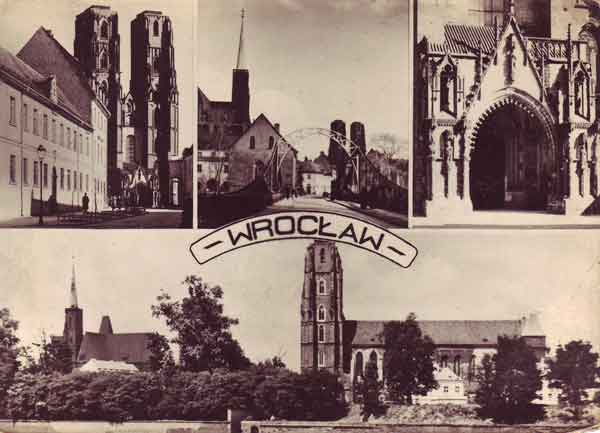

This is an old postcard from Wroclaw, Poland (formerly Breslau), created by someone with a natural, probably unconscious appreciation for urban design, someone who wanted to show you, progressively, just what you would see on the ground as you approached the center of his venerable city. In the bottom view, you are nearing the 'Cathedral Island'; the Cathedral is on the left, St. John's church on the right. To get in, you'll have to walk along the Oder River a bit, then cross the Cathedral Bridge (top center photo; note how the grouping of the church towerschanges). Carry on, until a bend in the street reveals the façade of St. John's (top left), and finally, the focus narrows onto the church's carved portal (top right). There is one striking and rather unexpected difference between formal and informal design. In formal compositions, what you see at first glance is what you get. Imagine yourself on a great boulevard like the Champs-Elysées. At one end is the Place de la Concorde, with its obelisk, at the other the Arc de Triomphe. As you walk up or down the street, the composition does not change. Informal design may lack the obvious grandeur, but it can offer a far more complex experience, what Gordon Cullen in The Concise Townscape defined as 'serial vision'-or what the clever architects who employed it in Disneyland called an 'arrival sequence'. Formal design is a static composition that works strictly in three dimensions. The dynamic compositions of informal design add a fourth, the element of time. A gateway closes the view as you approach it, and as you pass through it, it reveals something new. A street jigs and bends, and there is a sense of unfolding, of being drawn onwards through a composition— 'I wonder what's down there?' Another key to informal design is the element of surprise. In Rome again, you may remember winding your way through a web of twisting medieval streets and, on turning a corner, suddenly coming upon a generous piazza with the one-and-only Trevi Fountain for a backdrop. Surprise. (by day, the crowd of tourists might tip you off in advance; it's better at night, when the first hint is the incongruous sound of a waterfall in the middle of a quiet Roman neighborhood). Try to imagine the Trevi set in a huge piazza near the train station, or along any busy street. It would lose all its effect, and neither Romans nor tourists would care to linger around it. St Peter's Square at the Vatican, the vast formal conception designed by Bernini, originally lay in a similar warren of old streets, and offered the same contrast, the same surprise. In the 20's Mussolini had his architects clear a space for an axial road, the Via della Conciliazione, to open up the piazza and connect it to the Tiber. The Duce (like all dictators, perhaps) could only think in terms of formal design—but the genius of Bernini's original plan was lost, along with the surprise. Surprise also happens when a line or a pattern is maintained through a change in intensity or scale. Walk down Nurimaniye Caddesi, the shopping street of old Istanbul, and eventually you'll pass under an ancient arch and find that the street continues as the main aisle of the famous Covered Market. Islamic cultures seem to delight in this sort of inside-outside contrast in architecture. You may have seen the Great Mosque of Córdoba, with its ranks of columns and arches, but you couldn't have imagined the original effect. One side of the building, facing the courtyard, was originally left open (the Spaniards walled it up some time after the Reconquista). Originally,the rows of columns inside continued right out into the courtyard, turning into rows of orange trees. Graces like these are not often found in American cities. When they do occur, it is usually through accidents of topography, such as driving though the long, dark Fort Pitt Tunnel in Pittsburgh, and then suddenly emerging into the light to meet a spectacular view over the bridges and towers of the Golden Triangle. Pittsburgh is rich in visual surprise on the street level too, if only because the hills force its main streets to constantly curve and bend. Follow the parallel main drags of the East Side, Fifth Avenue and Forbes Avenue, to downtown from Oakland, Bellefield and Squirrel Hill, and watch the kaleidoscope change: distant buildings disappear and re-emerge, new cityscapes appear around every corner.

This example takes us to a basic principles of design: closure. The simple act of closing the view down a city street can make all the difference to cityscapes. As Gordon Cullen puts it, closure 'is the cutting up of the linear town system (streets, passages, etc.) into visually digestible and coherent amounts whilst retaining the sense of progression'. A void at the end of a straight street induces anomie—you don't know where you are. The information provided by a curving street engages the eye and helps us orient ourselves. More importantly, this 'cutting-up' helps lend the individual elements of the street system a sense of place. Of course, this principle doesn't work in every situation. Imagine midtown Manhattan with irregular streets and closed views. At this densely-packed skyscraper scale, closure occasions not delight, but claustrophobia, and the entire island would be rendered as unpleasant as Wall Street. The instincts of the commissioners who designed the 1811 grid plan may not have been so wrong after all. More likely, it was just New York's good luck. On any scale less intense than Manhattan's though, irregular streets are better, and it's our bad luck not to have many. If architects completely lost track of informal design, the landscape architects did not. The two broad styles of designing parks, the French garden and the English garden, make a perfect mirror for formal and informal design in cities. Since the 19th century the informal, English manner has held the ascendancy, even in France. America's greatest landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, worked entirely within this tradition, and a study of his methods reveals much of what is sound—and not just for parks. One of his most significant contributions was his organic approach, designing parks and boulevards not merely as isolated decorations, but part of the system of the city, both visually and practically. Another was the importance of composition, neglecting neither the broad view nor the details. One student of his work, S. B. Sutton, notes that 'Olmsted's parks almost never end at their edges. Sometimes by design, sometimes by implication, they send tentacles into the city; they suggest consequential dispositions of streets, traffic patterns and neighborhoods. No one understood better the idea of 'serial vision', the dynamic composition. As critic Tony Hiss, an observant rediscoverer of the city, reflected after walking through Prospect Park: 'A straight avenue, then a curve around a small hill, a larger hill and a lone beech tree, and something that appeared to be a cave at first but was really a Gothic archway....One part of experiencing places..has to do with changing the way we look at things, diffusing our attention and also relaxing its intensity-a change that lets us start to see all the things around us at once and yet also look calmly and steadily at each one of them'. Each part of the sequence drew him onward, from an impulse of delight. He experiences the sequence as it is: not a static composition, but a series of changing compositions, each one blending into the next. Hiss noticed some more of Olmsted's tricks: the use of landforming to completely isolate the more natural parts of the part from city noise and city sights, and the sublime trick of framing the Long Meadow, the longest natural vista in any American park, in that narrow cave-like archway for contrast and surprise. Art has had its way with Mr. Hiss, and here he has discovered the ultimate intention of Mr. Olmsted's art: something we used to call recreation. Like 'symmetry', this word has a hidden, original meaning: 'mental or spiritual consolation'. In this sense it was a favorite word of Olmsted's; he hoped his designs would prove useful in restoring body and mind, and calling the soul to higher things for a sweet minute amidst the hurly-burly of a big town. But nature isn't mandatory for this-as anyone who ever walked the streets of a medieval town can attest, there is something in the buildings and monuments themselves that arrests the attention and takes one out of the everyday whirl. An aesthetically impoverished nation may think this is only a tourist experience, but it is really an experience of place, something the citizens of a well-built town can enjoy every day. |

|