227 what railroads did to american cities

Be careful when you propose a change in a country's transportation system,

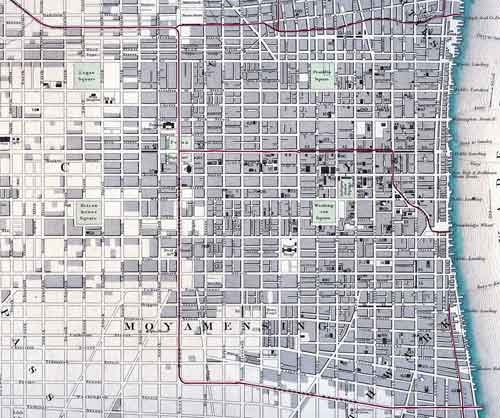

because you never know what might happen. Here's Philadelphia

in 1840. Less than a decade after railroads came to the city, there are

tracks cutting the central Penn Square into three pieces, and running

right down the middle of the main streets, Broad Street and E. Market

Street. Steam trains plow through the business district and many residential

neighborhoods. A line from the Delaware to the Schuylkill (top of map)

is attracting industry, and assuring that the areas around Logan Square

and Franklin Square nearby will never develop to their full potential.

The coming of the railroads reshaped America's cities in ways that no one could have foreseen. The first freight terminals began to appear in the 1840's, leading to concentrations of warehouses around them. But railroads also meant the first step in the decentralization of work. Besides the firms that located along tracks, and shipped from their own sidings, the number of scattered freight terminals in larger cities decreased the importance of the previous single central terminal-the port or river landing. So important were the railroads, that from the early days the law usually allowed them to lay out lines and yards in cities wherever they pleased. Even with that, purchasing urban land was a considerable expense. The companies, not the cities, planned out new corridors, and naturally they built them in the cheapest and most rational way possible. It meant the destruction or mutilation of many old neighborhoods—often financed with public funds, as in the building of the Interstate highways a century later—and it helped begin the dispersion of the middle and upper classes to the first suburbs. The railroads, of course, also helped provide the means of getting them out there. Ask Philadelphia about the way railroads disfigured cities. On the above map,you can see how a rail corridor lined with industry stretched from the Delaware to the Schuylkill just north of Center City. The partially completed line south of the center, through Moyamensing and Southwark, would be in place by 1860. Between them, the two lines completely cut off the centre from its surrounding neighborhoods. An expansive, attractive and populous city center is always one of the preconditions for urban life at its best. Because of its carelessness in allowing Center City to be strangled by rails, Philadelphia was doomed by 1860 to have only a relatively small one—small compared to Boston and Manhattan, where accidents of topography, and a little foresight, kept the growth areas clear of tracks and yards. Early on, New York banned steam trains below 14th Street; by 1870 the boundary had moved up to 42nd—that's why Grand Central Station is there today. Other cities' experience was more like Philadelphia's: major railroad centres such as Atlanta or Chicago, where the central area was even more closely circumscribed than Philadelphia, or Pittsburgh, where it was hemmed in by hills and rivers, and completely choked by tracks, heavy industry and slums. Some cities were more fortunate, such as St Louis, where economic necessity placed most of the tracks and yards across the river in East St. Louis, Illinois, starting that community on its career as one of the most depressing towns in America. As a matter of course, most cities lost their shorelines or riverfronts to the tracks, condemning some of the most potentially attractive residential and recreational sites to a career in industry. Most of the stream valleys got them too. And if a city should be so fortunate as to possess any parkland, it would be a prime target. What one enlightened administration created, its successor might easily give away to private interests. Philadelphia's Fairmount Park was a landmark of American city-building, but this did not stop later administrations from slashing six miles of track across it, on both sides of the Schuylkill. In Washington, tracks were even built through the Capitol Mall, with the blessing of Congress. As in New York, railroads always tried to lay track down city streets where they could, to avoid land purchases, and sometimes with the hope of making extra money by picking up riders through town. Atlanta, the south's premier railroad town, allowed them to go anywhere, regardless of smoke, noise, cinders and sparks. So did Chicago, and smaller cities such as Syracuse, where all the big passenger trains rolled right down Washington Street. In Dallas, the Pacific Avenue tracks through the heart of downtown were not removed until the 1920's. Not all citizens agreed with the divine necessity of railroad laisser-faire. One of Philadelphia's bigger commotions of the 1840's, the Kensington Riot, was sparked by a corrupt council's attempt to give a railroad a right-of-way down a neighborhood's busy main street. In the end, we learned that rail traffic needed to be separated from the fabric of the city, but getting the job done would take over a century. And as we see in Philadelphia, the damage that a new transportation system could do at its inception, is something that is not repaired even today. |

|

|