235 the vans' empire

The twentieth century in America will be remembered as the time when the economy, and indeed almost all aspects of national life were consolidated, homogenized and brought within the purlieu of large organizations. The previous century gave us political machines to manage our public affairs, and giant corporations to move us around and provide us goods from iron to beef. Now, reformers replaced the machines with larger and more costly public bureaucracies; chain stores conquered the marketplace and the corporation idea was extended to every field of economic activity. So too in city-building. Previous decades had managed very large developments, commercial, residential or industrial. But the real spirit of the new century in urban development would have its first and most spectacular manifestation in the mature, forward-looking boomtown of Cleveland. The story's worth telling. Orris P. and Mantis J. Van Sweringen were farm boys who grew up on the eastern edge of Cleveland, in what would soon become the agglomeration of suburbs called 'the Heights'. In their early twenties at the turn of the century, they were already buying up choice land. They took out options on the lands around the old Shaker colony in North Union township in 1905; about the same time they changed their names to include the 'Van', which couldn't have hurt business any. Business was in fact bubbling along. The Vans, as everyone in Cleveland called them, soon controlled over six square miles of contiguous land in the newly incorporated village of Shaker Heights (once the site of a Shaker community), and they meant to transform the whole of it into Cleveland's elite suburb. After the interruption of World War I they went to work in earnest.

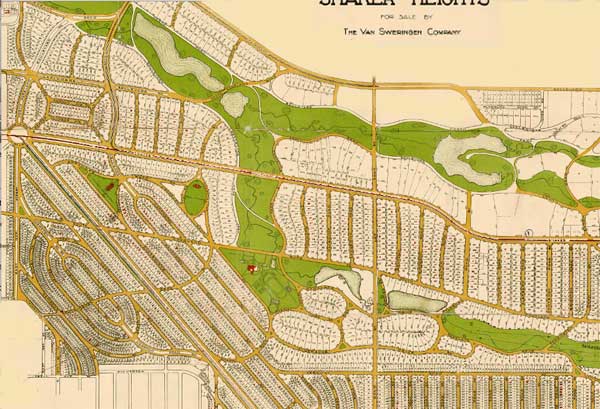

The first sections of Shaker

Heights, Ohio to be developed, c. 1920. The circle at upper left would

eventually be the site of Shaker Square.

Shaker was entirely in the tradition of such 19th-century developments as Llewellyn Park and Riverside, only on a much larger scale; at its height the suburb was home to 35,000. The curving roads and ample tracts of woodland are admirable; less so is the rigid class grouping. From the lot sizes on this plan, it's easy to see how the less prosperous residents were concentrated on the streets to the west and south, away from the parks. 'Less-prosperous' is relative, of course; in its prime Shaker Heights was the wealthiest municipality in the United States. Shaker Heights is the sort of place that inspires New Urbanist planners of today, but when it was built it had no bars, no blacks or Jews, and no corner shops where young people might loiter on the sidewalk. The Vans drew up restrictive covenants, as every other developer did, but also strict architectural standards for the purpose of enforcing a tasteful if somewhat numb conformity—a Frank Lloyd Wright Prairie house would never have been allowed in it. The Van Sweringen Company's promotional literature boasted: 'All that conserves home-spirit is cultivated; that which is inimical is to be barred'. Typically, a big part of the attraction was an independent school system, for the sake of status and class segregation, even though Cleveland's schools at the time ranked among the nation's finest. Where their new suburb met the city, the Vans built Shaker Square, the second major planned shopping center in America (after Jesse Nichols's Country Club Plaza in Kansas City), and they surrounded it with an entire new neighborhood of apartment blocks. Running through the square, on Shaker Boulevard, you can see the tracks of the rapid transit line that was to make the whole plan work. From the beginning, the Vans knew that Shaker would never be sufficiently profitable to them unless it offered some rapid rail service to downtown, five miles away. The streetcar lines were slow, and they ran through neighborhoods full of Hungarians, Italians, Czechs, Blacks and Jews. Local rail companies wouldn't cooperate, so the Vans planned to build a line of their own. Acquiring land for the right-of-way through the industrial valleys took years. Much of it belonged to the Nickel Plate Railway, and its owner wouldn't sell. So the Vans bought the whole Nickel Plate. Credit in the banks of Cleveland and New York was always at their service. But things were getting a little out of hand. Within a decade the Vans made themselves the biggest rail barons in the country, with control of the Erie, the C&O and 21 smaller lines, as well as over a hundred other corporations. The newspapers hailed them as the wonder boys of American capitalism. Now that they had their right of way, they only had to find a terminal for the line. Long before, they had assembled some land on Public Square, the city's center. At the time, Cleveland was planning a long-delayed union station at the northern end of Daniel Burnham's Mall. The Vans however assembled more land on Public Square, and used their influence to gain the support of the other railroads for a plan that would integrate the rail station with their rapid transit lines. They won, as they always did. And as always, their ambitions were already churning around the next step. Soon, the Terminal was envisioned as a city within the city. The city's biggest hotel, which the Vans had just built, was incorporated into it; a major department store signed up, as well as corporate commitments for a ton of office space. Uncle Sam threw in a new Main Post Office. The first architectural plan showed the Terminal topped by a modest tower and cupola. But in the giddy atmosphere of Cleveland's 1920s, this idea pupated and emerged as the 708-ft Terminal Tower, at the time the second tallest building in the world. Three more office buildings were grouped behind it, set over America's biggest parking garage. The pharaonic works in Cleveland captured the nation's fancy, and they would soon be emulated in such megaprojects as Cincinnati's Carew-Netherland complex and Manhattan's Rockefeller Center. The Terminal Tower was nearing completion when the stock market crashed in 1929. The Vans' financial empire, built on debt and an unfathomable web of interlocking holding companies, imploded soon after. The brothers went from a net worth estimated at three billion dollars to about $3,000, and both were dead within seven years. Toting up what the great bust left behind, we find a suburb of 25,000, half of Cleveland's surviving rail public transit, a national landmark planned shopping center, commercial space enough to employ 20,000, most of downtown Cleveland's retail, another national landmark tower and quite a bit more—nothing less than the largest, most sophisticated, completely integrated work of urban development in the history of the United States. Shaker Heights was built to last, and it remains an elegant neighborhood today; the maples and oaks the Vans planted in their thousands are tall and gorgeous. Their tram line now makes up the Blue and Green lines of the Cleveland RTA, though their end point, the Union Terminal under the Vans' great tower, isn't a railroad terminal at all any more, but a shopping mall. Real estate and development giant Forest City Enterprises, the current owners of the complex, keep it all in top condition; indeed they have spent considerable treasure on the buildings, money that would have brought in bigger profits elsewhere, restoring old glories and even adding new. The Terminal Tower (now stuck with the rather numb renaming of 'Tower City Center') remains the landmark and symbol of the city. I'm rather fond of it myself; my dad delivered mail in it. There's still one question left to ask, the one that must always be asked. Was the Vans' empire good city-building? An argument to the contrary would probably first mention the architectural mediocrity of their far-flung works. But their Neo-Georgian theme for Shaker Square and the apartments that surround it do give the area a distinctive look, one that is appreciated today. The same is true of the Terminal Tower. It is absurd, preposterous; its wedding cake top (which was copied from New York's Municipal Building, and in turn provided the inspiration for the Moscow University tower and a score of other Soviet skyscrapers) resides in the upper stratosphere of kitsch. We all love it. The real case against the Vans lies elsewhere. First, consider that their spectacular financial collapse destroyed the investments of many thousands of Clevelanders, helped take down at least one big bank, and contributed more than any single factor to the city's dramatic loss of economic power and confidence in the Depression. Next, imagine the effect that the sudden appearance of an elite quarter, with room for roughly four percent of a city's entire (metropolitan) population must have had on the neighborhoods already built. The upscale overbuilding that made such a big bust in the Depression did indeed jolt the entire city. Shaker was New and Improved, and it enticed several thousand families of the upper and upper-middle classes out of the old neighbourhoods along Euclid Avenue, once the city's world-famous 'Millionaire's Row, and especially out of the East End, the area now known as Hough, helping start those areas down a spiral of decay and disinvestment that would culminate in the Hough riots, only four decades later. The Terminal complex worked a similar kind of evil. Its sheer size had an effect that dampened and distorted development in the city center for decades. Site planning was disastrous. The rude interruption of the Depression left a wasteland behind the grand façade on Public Square. Gaping holes, rotting board fences, vacant lots and one hideous 220-ft blank brick wall lasted for decades (the wall's still there). More than fifty years later, some of the street-level shop fronts on Prospect Avenue remained unfilled. Outsiders have not always been impressed by the Vans' vision. Architectural historian Dell Upton (in Architecture in the United States) believes that their system, encompassing so many urban uses and needs in a single package: ...contributed to the breakdown of the larger city system. It was possible to do all one's business and return home without ever setting foot in the city itself'....Moreover, the diversity of a real city was sacrificed to corporate considerations of profit and public relations. The seedy elements that every city has and needs—the zones of transition and humble services that accommodate the poor workers who make a city function—were excluded from these sanitized mini-cities. |

|

|