157 great american nutjobs

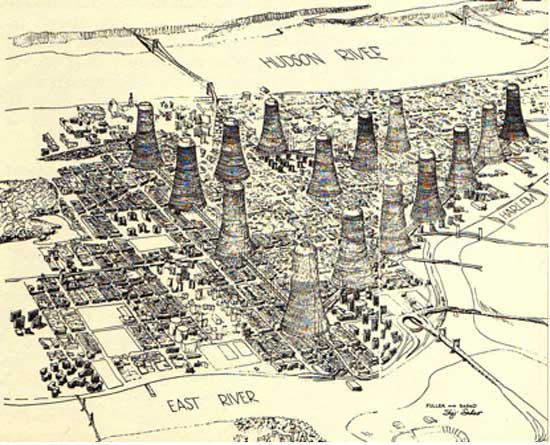

Buckminster Fuller: New Harlem

America might not have even needed imported Modernists; in the 30's some native minds were already aiming for the same hell in separate handcarts. Jefferson's long-delayed revenge on the evil Hamiltonian city could never have come from Europe. It was supplied by America's greatest architect, and also her noisiest anti-urban crank, Frank Lloyd Wright. A farm boy at heart, despite his flashy clothes and his famous red Lincoln Zephyr convertible, Wright just couldn't stand the thought of people living close together. Once, in Pittsburgh, he was asked what should be done for the city in the postwar era, and he said 'abandon it'. Like the Modernists, Wright thought of himself as a 'total architect', a master builder capable of redesigning our entire world. He would certainly have been capable of putting Pittsburgh out of its misery, had any government been dizzy enough to let him try. Wright had his own vision of the future after the death of cities. The model and drawings for 'Broadacre City' are sacred relics in the hands of the Taliesin Fellowship in Wisconsin, though the ideas behind it are discussed in a later book, The Living City. Encased in this fantastical, almost unreadable work is a basic idea of pure integrity, the thought of a true American original. Once we get to the core of the idea, we find Jeffersonianism carried to its wildest extremes, and motorized. Explosive sprawl as we know it is exactly what Wright intends, along with a way of life totally dominated by the automobile-at least until the personal helicopter is perfected; Wright mentions these often, and includes them in some of his drawings. Only Wright's weighty reputation has prevented critics from mentioning that The Living City is incomprehensible drivel, set in the prose of an inspired junior high school boy on amphetimines. Wright admits as much in a remarkable forward, and apologizes for it. Broadacre is a 'countrywide, countryside city', where everyone gets a lot of an acre or more, up to ten acres for farmers, and the home is a 'harmonious feature of an unviolated environment'. Violated or not, there is no escape from it. Broadacre City takes up all inhabited land, in an endless, undifferentiated sprawl with schools, factories, farms and everything else scattered randomly across it. There are no centres, because there is no society, rather a strange melange of rugged individualism and socialism, where small is beautiful and corporate capitalism has ceased to exist. Strict land-use planning and a governing caste of wise, benevolent architects would make it all pretty. It's clear from the model and drawings that Broadacre City differs little from the sprawl that we have actually built in our fringe areas. Both show the same rejection of urbanity and total disregard for design, and both point the way to our final mutation from a nation of stout yeoman farmers like Wright's Uncle James, on whose farm the architect spent fondly-remembered summers as a boy, to a nation of stout yeoman suburbanites, not exactly living off the land, but happily pretending to. Broadacres, according to Wright, is about the 'Sovereignty of the Individual.' The only thing missing in the drawings is the platoons of automobiles that everyone would need to get around. In the same vein, we had Buckminster Fuller, inventor of the geodesic dome and a man whose difficulties with human community and the English language were even greater than Wright's. Fuller caused a stir in the 30's with his ingenious, heavly-promoted '4-D' or 'Dymaxion' house, a modular, mass-produced abode which could be moved at the owner's whim to a new location by airship. First, the blimp would drop a bomb on the site, and then plant the unit's foundation in the resulting crater. Somehow, no investors could be found to take a chance on mass production, and Fuller dropped out of the public eye. He popped out of his lab again in the 60's, in the age of riots, with a plan to cure Harlem's ills by razing it to the ground, and rehousing the population into sixteen identical, hundred-storey buildings in the shape of nuke plant cooling towers. The fortunate denizens of New Harlem would never worry about rain, since their entire neighborhood would be covered by plastic geodesic umbrellas. This plan too failed to impress, but in the late, cloud-cuckoo-land phase of Lyndon Johnson's presidency you might have seen Fuller haunting the corridors of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, successfully cadging grants for feasibility studies to build new, floating cities. Just in case anyone ever needed one. How difficult was it for Americans to build well, or for public bodies to effect intelligent and sympathetic policy, when the visionaries, the best minds of the age, were lost in abstractions, enthralled by ideologies or decayed to antic lunacy? Across the board, the cutting edge of 20th-century thought had dedicated itself not to improving living communities, but to smashing them. |

|

|