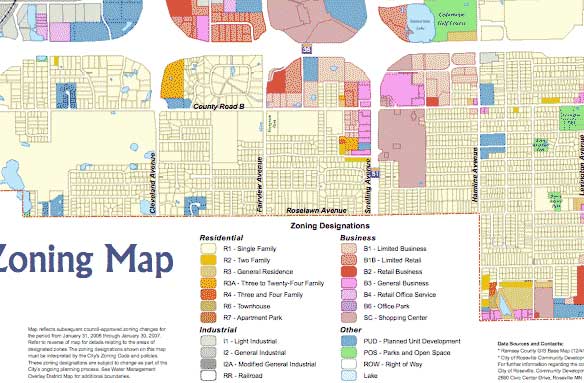

241 the origins of zoning

It's

just like Sim City: R for Residential, I for Industrial, C (here, 'B')

for Commercial. But in real life it gets a lot more complicated. This

is part of the zoning map of a Minneapolis suburb. The 'Zoning

Designations' in the legend, typical of zoning codes coast to coast,

show how intricate the segregation of land uses has become. Government

in its wisdom tells us where we may build a four-family apartment, and

where a five-family apartment. It divides commercial uses into seven

categories, each with its spatial pigeonhole. Why should it?

By 1920, it was clear that zoning was to be the city practical's magic bullet. With cities on both sides of the Atlantic booming and sprawling out in all directions, it was inevitable that some kind of land-use regulation would appear. Zoning was a European idea, first adopted in German and Swedish cities in the 1870's. In decades to come, however, most European countries would use it only as part of a comprehensive land-use planning that was much more ambitious and restrictive. The United States wasn't ready for that; it still isn't. The country did take to zoning, however, and has used it ever since as the major vehicle for regulation. Sadly, and typically, America had ulterior motives from the start. The first steps towards zoning appeared in California, and they arose less from a concern for orderly growth than from racial prejudice and exclusion. To the Californians, the real menace was not polluting industries, smelly stables or unsightly coalyards, but something far more dangerous and sinister—Chinese laundries. Neighbors complained that these laundries, however useful, had become hangouts for 'undesirables': that is, for Chinese. The federal courts threw out San Francisco's first attempt to outlaw them in 1886, but other California towns, starting with Modesto, soon found a primitive sort of nuisance zoning a viable alternative, and it was not long before they were applying the concept to less ethereal nuisances, such as whorehouses and slaughterhouses. Building on this experience, Los Angeles came up with America's first modern zoning ordinance in 1909. The movement was gathering steam; in the same year Boston's law governing building heights was upheld in the Supreme Court, and by 1913 several states had passed enabling laws permitting cities to control the location of industry. Meanwhile, in New York, necessity was pushing the project along, as two novel nuisances brought new factors into the discussion. One of these was the Equitable Building (1915), still standing, rather unobtrusively, among its bigger modern neighbors at 120 Broadway. When it was built, though, this squarish 42-storey monster, covering an entire block, was the talk of the city; it shut off window views, hid the sun and reduced property values and rents for blocks in all directions, besides overloading the surrounding streets and transit stops with its 13,000 employees at rush hours. The outrage over the Equitable led to New York's landmark 'setback laws', not merely regulating building heights, but introducing the more sophisticated concept of a 'building envelope' to assure some light and air for everyone. Meanwhile, up on Fifth Avenue, wealthy residents and carriage-trade shops faced an invasion of warehouses and factories from the growing Garment District around Seventh. The merchants' powerful Fifth Avenue Association was exhausted from years of using legal threats and bribery to keep the factory lofts at bay. Zoning offered a permanent fix, and the Association marshalled its considerable influence to push through a comprehensive zoning law in 1916, which became a model for other cities across the nation. The 20's brought the great breakthrough; zoning swept the nation, and by the end of the decade 60% of the urban population lived in zoned cities or suburbs. As Commerce Secretary under Coolidge, Herbert Hoover formed a committee to create a model state enabling act for zoning ordinances; his Division of Building and Housing designed model zoning codes for cities, and propagandized heavily for their adoption. The Supreme Court had already upheld Los Angeles's ordinance, which was largely limited to industry, but it still hadn't weighed in on the larger constitutional issues involved. When it finally did, in the 1926 case Ambler vs. Euclid, it would uphold zoning and take a big bite out of the perverse interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment that had upheld property rights against urban regulation since the Civil War. In the Cleveland suburb of Euclid, zoning had stopped the Ambler Realty Company in its plans to assemble choice land near the lakefront for industry. The arguments went well beyond this, however, and the famous case presented in the planning textbooks as a simple victory for progress and sweet reason looks a little murkier viewed close up. Ambler's attorney was no less than Newton D. Baker, one of America's most distinguished Progressives, an old protegé of Tom Johnson who had gone from the Cleveland mayor's chair to Wilson's cabinet. Baker made some telling points. Under Euclid's zoning the best parts of the village, fronting Lake Erie and in the wooded hills south of Euclid Avenue, were reserved for single-family housing, while 'All the people who live in the village and are not able to maintain single-family residences...are pressed down into the low-lying land adjacent to the industrial area, congested there in two-family residences and apartments, and denied the privilege of escaping for relief to the lake.' From the start, residential zoning had been twisted into an unprecedented legal mechanism for parcelling out the best land to the 'best people', but that was not the issue before the court. The decision, written by Justice George Sutherland, showed that the court was most impressed by the scientific pretensions of the planners, the 'commissions and experts...that the results of their investigations have been set forth in comprehensive reports, which bear every evidence of painstaking consideration.' It was all the more remarkable, that this decision would come from a court that spent most of the 20's striking down anything that reached them smacking of Progressivism, including even child labor laws. Sutherland, who also wrote the infamous child labor opinion (Adkins vs Childrens' Hospital) was a moldy mossback who had more opinions repudiated by later courts than any justice in US history. But he seems to have got the point that zoning was a new scientific fix meant to preserve property values. It was only to be expected that a suburb, and not a central city, would be the focus of the decisive fight over zoning. Even though the origins were in Los Angeles and New York, by the 20's the incorporated suburbs were the scene of the action in urban development, and it is precisely in this time that they were making themselves into the income-stratified preserves we know today. Zoning was the tool that crystallized the process; a majority of urban Americans today live in suburbs that were laid out in class-based divisions since zoning's advent. Ambler vs. Euclid would be the decisive step in the creation of the fortress suburb. The history of zoning illustrates how easy it was, how easy it would always be, to twist scientific pretensions in the service of class interest. The idea used to sell zoning in its early years was that it increases the safety of investments in land and development. Beyond that, the elitist motivations of the zoners shine through in all the literature of the time: we hear the apartment house considered 'a mere parasite', constructed in order to 'take advantage of the open spaces and attractive surroundings created by the residential character of the district'. For 'residential', read upper-class, single-family homes. And how scientific was zoning really? Washington got its zoning plan past the courts in the 1920's with the help of a local doctor who testified that flies from grocery stores might bring disease to children, and therefore by no means must shops be allowed to locate near homes. By presenting a complete package attractive to property owners and developers, the planners were able to enforce an overdrawn academic idea that has distorted the growth of American cities ever since: the rigorous division of all land into commercial, industrial and residential uses. A doctor or an artisan's right to carry on a business in his own home, as people had done since cities first began, was now subject to the vaguest whims of legal interpretation and neighborhood prejudice. The generation of immigrants who pulled themselves up by gathering capital enough to build a small neighborhood block with space to live above and a little rental income from a bakery below, would be the last, because such things were now banned as public nuisances. Eventually, the code would tell an artist he couldn't live in the loft space he found perfect for his needs, and it would create a world in which city dwellers have to walk ten blocks for a loaf of bread (or take the car). Considering zoning's origins, it was only natural for southern cities to immediately twist the concept into a legally sanctioned and scientifically managed model of apartheid. The first to pass an ordinance zoning a city into white and black residential areas was Louisville. The Supreme Court struck this one down (Buchanan vs. Warley, 1917) though not for any of the reasons that would seem obvious to us today. The justices found the ordinance violated the Fourteenth Amendment, by depriving sellers of property of the right to select their buyers. Federal Judge Courtney Westenhaver, who would later rule on Ambler vs. Euclid (favorably to the realtor, before the appeal to the Supreme Court) commented on the Kentucky case: 'And no gift of second sight is required to foresee that if this Kentucky statute had been sustained, its provisions would have spread from city to city throughout the length and breadth of the land. And it is equally apparent that the next step in the exercise of this police power would be to apply similar restrictions for the purpose of segregating in like manner various groups of newly arrived immigrants. The blighting of property values and the congestion of population, whenever the colored or certain foreign race invade a residential section, are so well known as to be within the judicial cognizance.' Buchanan vs. Warley did not deter southern segregationists. Cities continued to adopt ordinances that ordained the separation of the races by various legal mechanisms, and some of these managed to escape judicial disposal up to the 1950's. In 1920, a leading national planner made such a scheme for Atlanta. 'Industrial', 'commercial' and 'residential' were to be joined on the planning charts by 'white' and 'colored', though a thoughtful provision was made for the quarters of domestics. |

|

|