242 zoning reform

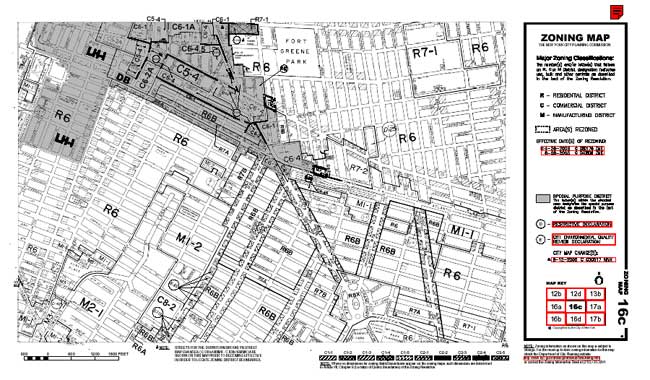

For those who have lost their capacity for outrage, or for more tranquil souls who are simply having trouble sleeping, New York's city government puts all its zoning codes and maps online. Here you will find everything you want to know about ULURP, the Uniform Land Use Review Process: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/luproc/ulpro.shtml If you haven't time for all this, the experience a citizen can expect from ULURP, in all its Kafkaesque horror, is summarized graphically here: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/luproc/lur.pdf When New York adopted America's first comprehensive zoning ordinance in 1916, the entire text came to 35 pages. By the swinging sixties, that was no longer good enough. Mayor Robert Wagner, with the help of Robert Moses, pushed through a new code in 1961. The architectural Modernists and the city bureaucrats shared the inspiration behind it; they assumed that one day New York would and should be a Corbusian vision of towers in the park, and they gave the city the power to micro-manage nearly every detail of design and construction. Today, with its accretion of amendments, the code runs to 900 pages. New York zoning is so complex that every project, no matter how small, requires at least one variance. The tortuous process of obtaining one contributes much to making building costs in the city a third higher than the national average, and it is helped along by newer and equally onerous requirements for 'environmental impact statements'; one of these for a big Manhattan project can cost as much as a million dollars to complete. Kafka himself would grin at New York's 'Unified Land Use Review Process'. Boss Tweed would have loved it. Everyone in city government, from the mayor down to the planning bureaucrats, can kill a building for one of a hundred reasons. That means developers, large or small, have to make nice all around. If New York's developers have become the biggest source of funding in local politics, it isn't because they are naturally generous, or even naturally corrupt. The system demands it. Though it wasn't designed for such nefarious business, the result might have been foreseen. If you want to build anything in New York, you're going to have to grease some palms. Naturally, the system has also created a new class of zoning lawyers-the guys who know the score, and know who to talk to. They have made themselves indispensable, and correspondingly expensive. The joke is, if builders are prepared to run the labyrinth, spend lots of time and lots of cash, zoning pretty much lets them do whatever they want. In New York, the wave of overbuilding that blotted out the Midtown sky over the last twenty years would not have been possible without the magical flexibility of the zoning and setback laws. All the features of a building are quantified, and the planners have designed systems of point scores. They'll give you 'bonuses' for plazas or indoor arcades and other amenities, and so reward good practices by letting the developer get away with bad ones, filling out more of the building envelope. They'll go farther still, and let you fill yet more space by purchasing a neighbor's air rights. As Ada Louise Huxtable put it, 'Now we have managed to 'reform', amend, and manipulate these controls to make it legal to do exactly what was outlawed in the first place'. By the 90's, nearly everyone agreed that the zoning code, with its horrific complexity and its invitation to corruption, was the biggest problem with development in New York. A new planning commissioner, Joseph Rose, took office in 1999 with plenty of brave talk about reform: `We are going to drive a stake through the heart of tower-in-the-park zoning and its trail of exceptions, caveats, and interpretive gymnastics'. Little or nothing has happened since. Why not? The system, it turns out, has plenty of friends. Not only the public officials and the lawyers, but the biggest developers do well from it, even though they have to pay. They have the money and connections to find their way through. Outsiders and smaller operators do not. Regulation created privilege. As early as the 30's it had become clear to everyone in real estate that zoning was nothing more than a means of maintaining the status quo, of protecting the investments of the upper and middle classes. As one expert put it, 'nine hundred and ninety nine parts out of a thousand [of zoning codes] is what the average informed real estate owner of that district will stand for'. And even at that early date, the tradition of changing the zoning whenever a developer needed it changed was widespread. In the 30's, Chicago was already making over a thousand amendments to its zoning each year for individual From its inception, zoning had managed the difficult trick of being harmful and toothless at the same time. Zoning's purpose was supposed to be preserving investments and neighborhoods, and yet over 70 years our massively zoned cities have seen the greatest wave of decay in urban history. There is no evidence, from anywhere, that zoning has given any declining neighborhood an extra minute of time before its doom arrives. Today, the Victorian fantasy of perfecting communities by hygienic planning and segregation of land uses may be dead, but the machinery it created continues to impoverish and disfigure our cities. Zoning, from its beginnings as an objective and scientific method of determining land use, has become a refuge for every sort of unsavory special interest. It contributes to sprawl, and to the blandness and conformism of our neighborhoods; it raises housing costs for everyone. Its highest purpose today is enforcing residential segregation by class. In recent years, this concept has been expanded to encompass something so diabolical that only Americans could have invented it. Suburbs now commonly apply their land use powers to discriminate against families with children-one critic calls it 'vasectomy zoning'. The motivation of the jurisdictions that do it is plain; keeping children out improves their finances, by lowering their costs for education. So growing fringe suburbs give big incentives to developers who build condos with one or two bedrooms, and put obstacles in the way of those who wish to build them with three or more. It is easy to see why suburban governments, like New York and other inner cities, appreciate zoning as it is. Local governments, in fact, will always be the biggest obstacles to reform. Despite the glaring iniquities, opportunities for corruption, and ample proof of the harm zoning does, until recently experiments in reform have been limited and few. The courts, an apparent alternative, have been tried many times. Several omnibus anti-zoning suits have gone through the legal process, and all of them failed. In its last major zoning decision, in 1974, a liberal Supreme Court ruled that a town could forbid three or more unrelated people from renting a single-family home. But times are changing. Planners, architects, journalists and scholars bring up the subject with increasing insistence, chronicling zoning's many evils and working out ideas to fix it. Most surprisingly of all, the push for reform is being led by two groups of people you wouldn't have imagined finding on the same side of an issue ten years ago: New Urbanist designers and philosophical conservatives. The New Urbanist obsession with zoning is not hard to understand. When architects such as Andres Duany first dreamed of recapturing the humanity of older, traditional neighborhoods, they soon discovered that building new developments that way would be illegal almost everywhere in the country. They have been fighting to slay the beast ever since. Duany himself has worked out a complete framework for a new kind of zoning. It's called the 'Transect', and it classifies zones not by the old categories, but in degrees of relative intensity, from wild country land through sparsely-populated 'edge' zones and on to the high-intensity 'core' of an urban downtown. Each has its character, and a set of design rules appropriate to it. Creating livable, walkable neighborhoods is one key to his approach, but just as important is reclaiming the old right people once had to work at home. As Duany puts it, our style of city-building 'has been selling the little house on the prairie for decades, but ignoring the be-your-own-boss aspect' of the American dream. Other New Urbanists have worked out their own schemes, and like Duany's all of them seek to move zoning towards a concept based on design, not abstract technical rules. The zoning codes for new 'Traditional Neighborhood Developments (and more than 200 of these have appeared in recent years) use design to promote walkable, pedestrian-friendly environments on the street. They narrow streets, and relax rules that mandate parking, while tucking away parking lots off the street front. To favor life and diversity, they are also considerably more lenient about allowing mixed land uses. TND zoning codes, often called 'Smart Zoning', concentrate on making zoning tie in with public transit, giving special treatment, and higher allowable densities, for areas around rail stops, or in 'transit corridors' along major routes. Best of all, the New Urbanist codes are simplicity itself; Duany likes to boil his down to something that, with illustrations, can fit on a poster. New Urbanist zoning is a revolution that has already begun; in the last ten years dozens of towns have worked some of these principles into their codes; they're mostly small towns, though the list includes progressive big cities such as Austin and Columbus. Right now, most of these are tentative, experimental steps, and in some cases the new codes are 'optional', meaning that in case of conflict with the older codes, the more restrictive ones apply. Conservative thought on zoning generally favors a minimum of political intervention in landowners' choices, a maximum of stability, and an embrace of reform, in decreasing onerous regulations but also in some very unexpected and progressive ways-such as forcing developers to pay for new infrastructure. They would like to see a zoning that is less rigid and rationalistic, more market-oriented and adaptable to change. They point out that navigating the zoning process and meeting its requirements can add 20-30% to the cost of a home or a commercial building, and that the value to the community of that expenditure is small indeed. Market-oriented scholars have come up with plenty of ideas for reform in recent years, some of them unfortunately on the borderline of daffiness. There is 'performance zoning', in which the rights to create nuisances or to develop could be bought and sold, like the current market for pollution credits, as well as proposals to privatize the entire system, and leave all land-use decisions to be made by those paragons of public interest and serious thinking, the homeowners' associations Under 'Market-Oriented Planning', the entire question of nuisances would be left to the courts, in a way modeled on the U.S. tort system. Though plans like these would be Christmas for lawyers, it is difficult to see what good any of them would do cities. The most encouraging conservative ideas are the simplest. Here, in outline, is a plan for reform by George W. Liebmann, from Regulation Magazine. Liebmann calls it a 'Developers' Bill of Rights':

Nearly all the items on this list are also part of the New Urbanist agenda. This growing convergence of ideas is one of the most encouraging things to happen in recent years. Comparing these two approaches, the market-oriented notion of reform puts a higher emphasis on freedom, the New Urbanists on shaping urban form. Though New Urbanists' may be quite serious about discarding bad regulations, their prescriptions in some ways can actually be more restrictive than current zoning, with design guidelines and determinations on the size and shape of individual buildings. They are architects, after all. Some of them call for a huge degree of architectural control over their developments, down to the smallest details—a common feature of the City Beautiful-era suburbs they emulate. For an extreme case, take a look at Windsor, Florida, an elite golf resort that allows no basketball hoops, no trellises, no clotheslines. The architectural review commission can tell you, among many other things, what color you can paint your window trim and what sort of shrubs you can plant. In almost all their projects, they still segregate even small apartment buildings, as if their residents were lepers. Some of these outrages aren't entirely their fault. The segregation of apartments, long a part of zoning dogma, has passed into common custom, and designers would have a hard time getting backing for any plan that did not include it. But it isn't difficult to see how easy it would be to use design guidelines as a tool for maintaining single-class enclaves. It would be tragic indeed if we were to finally defeat zoning, only to replace it with an equally cumbersome system, one that perpetuates the same evils. |

|

|