021 basic units: streets and squares

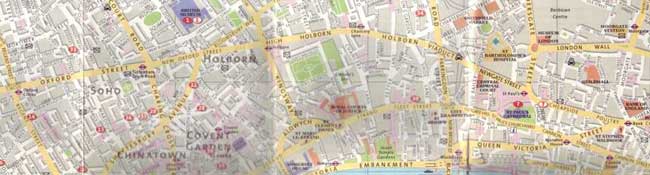

Heading out from the center of the City of London, on the old high road towards the west, you're on a street that changes its name seven times before you travel a mile on it: Poultry, Cheapside, Newgate Street, Holborn Viaduct, Holborn, High Holborn, New Oxford St., Oxford St. This is common for any European city, but it can be exasperating to us tourists; we think they're doing it just to tease us. In fact, this old curiosity points up a significant difference between two ways of looking at streets. To the medieval Londoner, thinking within the tradition of informal design, a street was more like a room in a house than merely a conduit for traffic. In the Queen's English, an address is still described as 'in' a street; we speak of being 'on' a street, as if we were on a conveyor belt. The old street had a sense of place, and a character, even if were only one block long; the piquant names of Poultry and Cheapside give away their ancient role as the city's busiest marketplaces. Venetians, true conoisseurs of urban spaces, developed a rich vocabulary of words for them. We have little more than 'street' and 'avenue', between which there is seldom much difference, along with the occasional square, boulevard and alley. In many towns the names are applied solely for practical convenience in orientation; streets run east-west, avenues north-south. In Venice an open space, according to its size and character, might be a piazza, a piazzetta or a piazzale, a campo, a campiello or a piscina. A street, besides the common Italian words via, viale, vico, vicolo, corso and largo, could be a corte, fondamenta, ramo, rio, rio terrà, calle, riva, molo, ruga, sacca, salizzada or sottoportego. It's rather like the Eskimo's fifty different words for 'ice'; each of these is a particular kind of a street, and e urban Italian enjoys making fine distinctions. Compare this rich Old World heritage to the utilitarian way we imagine and design streets. The very first urban street laid out in the old Northwest after the Northwest Ordinance of 1785 was at the new foundation of Marietta, Ohio. It was 175 feet wide, enough for twenty lanes of traffic, had there been any traffic (incidentally, if you've ever wondered why so many small American towns have such impossibly wide streets, it isn't that they expected to grow up into big cities, only that a big team pulling a wagon could turn around in them—practical, though as anyone who has travelled around small-town America knows, it can make the center of a community seem a desolation) Now here's an irony: that intimate, convivial, medieval series of urban rooms in London is of course now a single, busy traffic corridor, little different from any American downtown street. Nobody sells old clothes in Cheapside any more, or broiler hens in Poultry—the Bank of England's there instead. There's a lesson here, a reminder of a basic truth of urban design: cars and people don't mix. Ever since vehicles travelling at speed began to take over the public way—not at the dawn of the automobile era, in fact, but back in the Paris of the 1600's, when the wealthy began riding horse-drawn carriages and the sprawling city knocked down its old walls and turned them into the first 'boulevards'—the street has presented the essential modern problem in urban design. As long as city-builders continue to think all streets are alike, that problem will never be solved. It would be better to conceptually divide streets into two classes, those where traffic dominates, and those dedicated, more or less, to people, where motor traffic is tamed and grudgingly tolerated. These days, a healthy city has need of both. We've been through this problem once before, with the railroads. In the early days, lines were often laid out right down the middle of city streets. Eventually, everyone came to agree that cities worked better when trains got their own dedicated rights of way, separated from the calmer world of pedestrians, horses and carriages. Similarly, a big task for urban design since the beginning of the automobile age has been channeling the roaring flood of traffic away from the places where people live, work and play. The controlled-access freeway, first envisioned in the 20's and crystallized into a uniform national design by the Interstate Highway Act, was intended as a permanent solution to the problem. We can see now that the manner of design chosen was a very poor one, and also that the urban Interstates provided only a partial solution. When the predominant means of getting around changed from foot and trolleys to cars, the old commercial street we enjoyed for centuries for our business and shopping suddenly became a hellhole of noise, smoke and danger; it transformed itself from an urban-scale, convivial urban room to a traffic chute, lined with strip malls and parking lots. It won't do. Getting our cities right again will mean not only design solutions for new towns and neighborhoods, but retrofitting old ones in a way where people and cars both have their place.

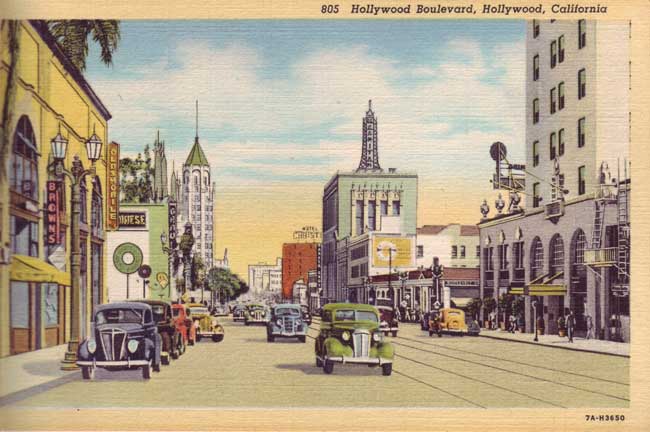

Now, how do we look at streets? A postcard publisher in 30's Los Angeles evidently thought this view down the famous Hollywood Boulevard worthy of inclusion among the sights of the city. In truth, this is just another long, straight American street, albeit brightened by some delightful architecture and Angeleno buzz (note Grauman's Chinese and the El Capitan theaters in the center). We think it worthy of inclusion here because it demonstrates a subtle but important point about design. You'll notice how the photographer took his shot from a position not in the centre of the street, but just off to the left. We've all seen plenty of photos of the Champs-Elysées in Paris. These are always taken right from the centre of the street, making the buildings along it form a symmetrical frame for the Arc de Triomphe at the western end. The difference between these two camera angles show two different ways of making a street into a real place—that urban 'room'. For the Champs-Elysées, design does the trick automatically. But if the Hollywood Boulevard photographer had taken the same viewpoint, the center of his photo would hold only a disorienting void—a poor composition for a photo, and a poor example of urban design. Instead, he used his art to make up for the art lacking in the street plan. He put in a little angle, so that the buildings on the right side of the street partially close the view; these add color and detail, and help give the street he portrays a sense of place. He also chose a spot where two buildings taller than the others (the El Capitan is one) subtly narrow the prospect. Nobody likes being in a void. We would never think of an open natural landscape that way, but somehow, in the man-made environment, a flattish mass of buildings that straggles off to the vanishing point makes us feel as if we're nowhere. A little bit of enclosure can put us more at home. There are other psychological considerations. In the 80's, for example, developers began building shopping malls with curving or angled paths, unlike the straight, rectilinear spaces of the early models. They had noticed the simple fact that in the old malls, people walking through have to make a conscious effort, turning their heads, to see what was in the shop windows. The new style put the windows right in the customer's line of sight, and actually increased sales. The same principle works on city streets. A street that isn't straight amplifies our visual knowledge of the city, aids in orientation and memory, and heightens the aesthetic experience of travelling in it, whether you're in a car or not. This makes a good example of how, as we learn more about urban design, rules gradually suggest themselves—not ironclad commands (for design is a gentle and flexible art), but welcome morsels of common sense. And even a long, straight American street has its qualities. Planner Kevin Lynch once isolated an important quality of the automobile-scale street, something he called the 'melodic line'. Imagine yourself in a car, traveling down an important thoroughfare. The scale of the buildings rises and falls in intensity; passing through different neighborhoods introduces new themes, new colors. Traveling towards downtown may be a sustained crescendo. You probably know a street in your city with a pronounced melodic line. Or think of, say, Fifth Avenue in New York. The melody starts with a strong statement: Washington Square and Stanford White's delicate arch. That theme reaches a crescendo at Madison Square, after which a second theme takes over, down the Fifth Avenue of Deco and modern skyscrapers that culminates at the Plaza. next comes a quiet and dignified strain bordering Central Park...and so on. Hollywood Boulevard, as it happens, possesses a good line. The downhill slope from its eastern, downtown end gives the motorist a glimpse over what is to come, prefiguring the crescendo reached at Hollywood's center, the area shown in the postcard above.

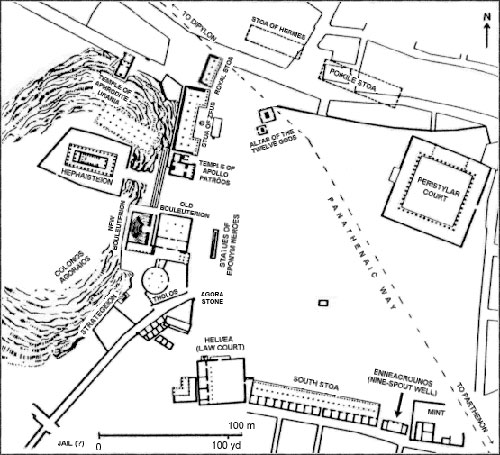

The Athenian agora (3rd century bc)

If you were looking for one particular item to stand as a symbol for western civilization, you couldn't do better than the public square—or specifically, the ancient Greek agora that is the mother of all our urban meeting-places. No other culture really has anything like it. All of them, of course, have marketplaces, as well as special spaces dedicated to affairs of the community, everything from the Pueblo Indians' kiva to the Campus Martius where republican Rome drilled its citizen army to the gurudwaras of the Sikhs to the sacred gates of old Babylon. But the combination of religious, political and commercial uses in a single space, and the long tradition of designing architectural spaces fit for them, seems to be uniquely western. A Greek agora typically had a larged sloped area, or even banks of seats, for citizens to assemble and listen to the orators. it had places for market stalls and law courts, stoas for the transaction of business, temples and shrines for religious ceremonies. Since then, the art of the agora has evolved considerably, though as cities have grown bigger the tendency has been to divide its functions among more than one square. In medieval Italy, free city republics such as Florence, Pisa and Siena assumed a bipolar form, with a sacred and a secular piazza: one for the seat of government and one for the cathedral. Medieval cities carried the art of urban design to levels seldom reached before or since, though the origins of most of their contributions lie in the ancient world. One was the enclosed garden, meant to supply a little contemplative peace amidst the city's bustle. The original inspiration came with the monastic cloister, with a form modelled on the old Roman villa. The cloister was equally at home in town or country, though it would eventually find another urban application in the quadrangle of university towns such as Oxford. The idea of a square as a strictly architectural feature was revived by the Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti, who laid down strictly aesthetic rules to govern its size: for example, the right proportion of a monumental building's height to the depth of the piazza that fronts it. After Alberti, architects and planners magnified the idea of the piazza; in the late Renaissance and Baroque eras, when the city itself was concieved as a kind of stage set for the decorous comings and goings of kings, nobles and clerics, the square's theatrical possibilities seemed even more important than its practical ones. Pope Sixtus V and his architects remade Rome, laying out new piazze punctuated with obelisks, points of orientation that visually tied the sprawling city together. Not long after that, the fashion for purpose-built residential squares appeared: the 'royal squares' of Paris, the Plaza Mayors of Spanish cities, the Bloomsbury squares of London. Other mutations and adaptations of the idea have followed over the centuries, and America has played a part too, from the commons and public squares of colonial New England towns to the 'plazas' in front of corporate skyscrapers.  The Parvis, La Défense

With the street become a traffic corridor, it is mostly left to the squares and plazas to perform the function of urban 'room'. Some of them do it better than others. Look at the recent experience of Paris. In recent decades, the city has completed several major city-building programs involving public spaces. In suburban La Défense, the government planners created a brand-new business downtown from the ground up. At Les Halles, in the city center, they eliminated the ancient wholesale food district and replaced it with a park over an underground shopping mall. Nearby, they built an ambitious and architecturally-acclaimed museum and exhibit space, the Centre Pompidou. For all its money and talent, Paris has a record of committing architectural cock-ups on a spectacular scale, and as urban spaces the first two projects proved resounding duds. La Défense is an immense concrete plaza, almost a half-mile long and randomly dotted with office skyscrapers of generally undistinguished architecture. The planners put all the life—all the shops and restaurants—underground, leaving the Parvis, as they call it (an old French word for an architectural square), an eerie, windswept void. Recent attempts to fix it by installing a few cafés are too little, too late. Nobody stays out on the parvis any longer than they have to. At Les Halles, the planners came up with a park they hoped would be intimate, on a human scale; it's chopped up into pieces, separated by walls and high hedges that disguise the entrances and ventilation ducts of the mall beneath. This park is such a failure, that after slightly more than twenty years the city is thinking of clearing it and starting fresh. What happened? Those intimate, enclosed spaces attracted mostly bums—not entirely down-and-outers, but also regular guys, sitting alone and enjoying the favorite Parisian pastime of thinking gloomy thoughts and drinking beer. Everyone else avoids it like the plague. We try to avoid rules, but it does seem that in almost all cases an urban public space requires transparency—literally, people must be able to see through it. The matchless urban observer William Whyte noticed this with Bryant Park behind the New York Public Library. A 30's remodeling had enclosed it, and in the 60's it became a drug supermarket. When the city remodeled the park, the problem was solved. Even in a genteel, completely safe city like Paris, many people feel a little nervous in the isolated corners of parks. Nothing could be more transparent than the 'Plateau Beaubourg' in front of the Centre Pompidou. Architect Renzo Piano made it nothing more than a bare rectangle, but with the Centre's opening the square became an instant happening, and it's still usually the liveliest place in town. What's the difference? Much of the Plateau's charm comes from Paris's traditional performance riff-raff, the bicycle swallowers, street mimes, fire-eaters, snake charmers and five minute portraitists. They're here, instead of at Les Halles, because the latter has no place for crowds to gather, and no way for prospective audience members to see them from a distance, through all the barriers. Parisians do not come just to see the bicycle swallowers. They like the Plateau so much that, even though Mr. Piano forgot to provide any benches, they find a themselves a piece of cardboard and sit right on the ground. There are just as many down-and-outers here as at Les Halles, but because it's wide open no one minds them. There's a reminder for you on how good urban design can bring people together, while bad design reinforces the subtle psychology of class separation. And also, a reminder of how good design can be something drawn in two minutes on the back of an envelope. Paris is a good city for looking at public spaces because it contains an example of nearly every possible type. We could mention the Place Charles de Gaulle (formerly Place de l'Etoile). That's where the Arc de Triomph stands, out in the swank 16th arrondissement. It looks good on postcards, but this Place is a nightmare for anyone who has to cross it. Thirteen busy streets empty into it, and to get through it requires crossing five or six of them. For motorists it's the world's biggest bumper car ride. How did this happen? Centuries ago, all this part of town was a royal hunting park.The rond point where the Arc stands now was intended as a spot where the king and his friends could wait and see deer crossing any of the long straight paths that intersected here. Baron Haussmann kept the street plan in his development of the new quarter, and even added more streets to pour traffic into the new Etoile. In doing so, the good Baron threw away two centuries of Paris design experience, expressed in old royal squares such as the Place des Vosges and Place Vendome, which only have two street entrances each. No one would begrudge Paris such an wonderful embellishment as the Etoile, but it is a mess, and when you create a mess in a big dense city it may take centuries to get it fixed. From examples such as these, we can see how designing squares to fit their purpose is important to cities. And we might agree on one basic principle: a square should have a purpose. Here's a brief catalog of what those purposes might be. Markets: Open spaces where things are bought and sold have been part of cities since the beginning of time (in fact, markets probably brought the first cities into being). For a century, American cities have been doing everything they can to discourage open markets, out of a twisted idea of 'progress'. It's well past time to reverse that trend. Other work functions: Today, they exist mostly as memories: open spaces that once were places of work, such as Baltimore's Inner Harbor; they survive as places for recreation, and also as testimonials, keepers of the community's memory—as do Boston Common and the public squares of New Haven and Cleveland, which began as common lands for the first villagers to graze their livestock. Political assembly spaces: Here, the heritage of the Greek agora survives best. They're not obsolete; even in the television age, every town should have a place like Hyde Park Corner, the spot in London dedicated to free speech, where improvers and millenarians of all persuasions still hold forth for anyone who'll listen. Union Square in New York served the same function a century ago, about the same time that Cleveland's great progressive mayor Tom Johnson dedicated the northwest corner of Public Square for the purpose. Johnson's statue stands there today, and it's still the traditional spot to begin demonstrations. The great size of Florence's Piazza della Signoria and Siena's Campo is a reminder that these civic squares once served not only for cpopular assemblies, but as drill grounds for the citizen militias. religious functions such as Piazza San Pietro in Rome, where the faithful come to receive the blessing of the pope. The civic center: A collection of public buildings built to embody the civic spirit of a town, or even a state. Pierre L'Enfant's Mall in Washington is the inspiration, and every state capitol green or county seat courthouse square can be considered a minor version. City Beautiful architects sought to make them the architectural centerpieces of cities. Jane Jacobs was opposed to civic centers; to her they represented the prime evil of modern planning, 'separation of uses'. She saw civic centers as dead zones outside working hours, and would have preferred to mix public buildings among the other uses of the city center, to promote life. Anyone who's ever seen an design disaster like the Civic Center of Los Angeles will immediately get her point, but in a healthy city with no lack of lively streets there is no reason to forbid an ensemble of civic structures. The downtown plaza: Dense centers and commercial nodes always have need of places for people to feed the squirrels, enjoy a brown bag lunch or just sit. They come in an infinity of shapes and sizes; they can be leafy or architectural. Sometimes they are planned, sometimes they appear spontaneously over time. In America, architects often care more about making them more show-off set pieces than useful and amenable to the people who live and work around them. Parks: The idea of an urban space for recreation certainly isn't new; only the concept of recreation has changed. To the ancient Greek, who had little interest in nature, strolling the shady stoas of the agora and conversing with friends and associates was relaxation enough. The first green spaces in cities were the parks of princes, a feature that goes back to the time of that famous gardener King Cyrus of Persia, or perhaps much further; the amount of access common people had to such spaces differs over time and place. Urban spaces that really brought nature into the city for everyone grew from these; in Europe, more and more of these were opened to the public over the 17th and 18th centuries. A park is essentially a big square, and it requires little more than trees, lawns and plantings. But from these simple elements a truly great art can be spun. America's greatest urban designer was not an architect, but a landscape designer, Frederick Law Olmsted. Alamedas: That's what they're often called in Spanish cities: a street with a pedestrianized central strip, lined with trees and carefully landscaped, with fountains and paths, like the famous Ramblas in Barcelona. Andalucian cities, Seville, Málaga and above all Granada have some lovely examples. These can be great urban amenities, though the fashion never really caught on in America. On a pedestrian scale, Baltimore's Broadway, Massachusetts Avenue in Boston's Back Bay, and some of the Kansas City parkways capture the idea, but in downtown locations they're rare. Some streets with medians currently narrow and neglected might become attractive alamedas, such as Cincinnati's Central Parkway or Detroit's Washington Boulevard. The idea might come in handy in many cases where a town wants to bring some life and character to a too-wide main street. Secluded spaces: Think of a church cloister or a university quadrangle; these served medieval cities well as a place for a respite from urban bustle. Their semi-public, semi-private nature tends to ensure calm and security, making them an exception to the rule about transparency mentioned above. Residential squares: If a king could have a garden, why not his subjects? That was the idea behind the invention of residential squares in Paris in the 1600's, such as the Place des Vosges. It was the kings themselves who initiated them, as real estate speculations for their own benefit. Residential squares dominated upper-class private development in many nations (including much of the U.S.) up until about 1850; the shared green in the centre was often private and gated. After that, people began moving out to more spacious locations, on lots that were little parks in themselves; the shared green in the middle was no longer necessary. But residential squares can achieve genuine architectural distinction, and I believe they're ripe for a comeback. Specifically, they might be the means by which families—not just singles content to live in converted warehouses—can be attracted back to city-center living. Architectural plazas: We'll agree with Mr. Alberti that significant buildings often need an open space, even if it serves no other real purpose. The corporate plazas in front of our downtown skyscrapers essentially perform this function. They are also legally required by zoning codes in most cases, to allow some light and air onto the street, though downtowns like Houston's which have no shortage of light and air, have plenty of them too. The old courthouse squares served the same purpose, as does City Hall Park in New York City—though we'll recall that New York, like most American towns, built its public buildings on publicly-owned parkland only because the city fathers were too cheap to buy a lot. Accidental squares: Cities with an informal plan can acquire a kind of square simply by accident: by the erosion, over time, of the surrounding blocks to make way for more traffic. That's the way it worked in the Middle Ages, and also in towns like Boston, where heavy traffic and an irregular street plan conspired to create Scollay Square. Such dubious squares can occur where two broad avenues meet at an acute angle, like Kenmore Square in Boston, or New York's Times Square.

Scollay Square, Boston. It might have become Boston's Times

Square, but Boston's peculiar Puritan demons eventually turned it into a

pure vice center instead, the famous 'Combat Zone' that

would be completely demolished, effaced from the city's memory,

and replaced with government buildings

|

|