201 the early american city

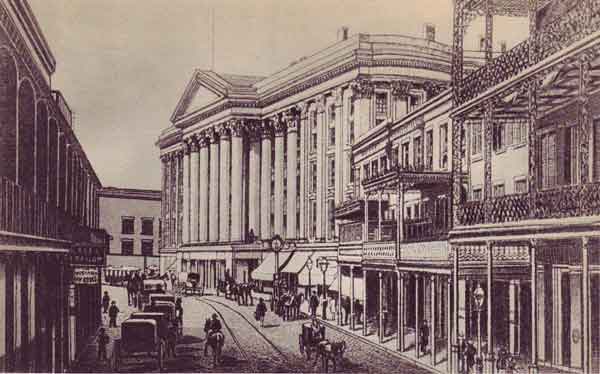

The St.Charles

Hotel, in the 1850's, set in the new commercial district the Americans

built across Canal Street from old French New Orleans. White-columned

monuments like this were the landmarks of downtowns everywhere, the

social centers for businessmen and politicos. This one, like the lovely

homes of the Garden District, was a statement on the part of the city's

new American elite—a way of saying to the French, we're cultured people too.

Looking at the blank grid on the map of an early American town, it might not seem easy to figure out how it worked, or where the various elements fit in. Really, you need only know where two things were located—the docks and the market—and keep in mind one fundamental principle: in the walking city, physical proximity to work and services was everyone's prime consideration. Almost without exception, towns before the rail era were located on some navigable waterway. The waterfront, centre of all trade and commerce also attracted most of the manufacturing; water offered power for mills, and the most convenient dump for wastes. Consequently, the streets around the docks will contain some of the oldest, poorest and most crowded tenements, along with plenty of boardinghouses, flophouses, labor exchanges, chandlers, and taverns. A block or two back from the wharves, depending on the size of the town, you'll find the new business 'blocks' of the merchants, with neat bands of painted signs under each row of windows, and projecting beams to hoist goods. In these embryonic downtowns, fine public buildings like New York's City Hall (begun 1802) or Charles Bulfinch's Massachusetts State House (1798) were still exceptional. The age of the Greek Revival put columns and pediments on exchanges, banks and hotels, while other city buildings tended to the homespun and utilitarian. In smaller communities, town councils would often simply rent space in a business block, and even state capitols showed little pretension to the monumental. Ohio, the first state organized in the Old Northwest, built its first one at Columbus in the modest, unadorned form of a New England meetinghouse, appropriate to the limited means of a young state, but also a reminder of democracy's roots. Lacking public buildings, the most prominent feature was the merchants' exchange, a symbol of the urban mercantilism of the day, and often the most ornate and expensive building in town; particularly impressive examples appeared in Baltimore, New York, New Orleans and Philadelphia, where the elegant cylindrical Merchants' Exchange of 1834 still stands on Dock Street. Clustered around the exchange you'll also find the banks, for which the model was the Corinthian-columned First Bank of the United States in Philadelphia (1796), initiating America's enduring association of classical aesthetic ideals with the custody of money. Your old map may give the location of these, as well as the leading hotels—not just to help the traveller find a bed, for these were also the closest thing most cities could manage to a tourist attraction, with domed rotundas and columned dining halls, a bar full of politicians, businessmen, and visiting commercial agents, and a lobby sporting velvet settees and splashing fountains to astonish the farmer on his day in town. One of the innovations of the age, and an important symbol for the commercial republic, these palaces held the starring role our downtown skyscrapers do today. They sprouted up like toadstools in boom times. Isaiah Rogers, the John Portman of his day, started the fashion with the 1828 Tremont House in Boston, and went on to design many others in the same limestone Greek Revival (often painted white), like the Burnet House in Cincinnati or the Planters' Hotel in St Louis. The latter, with its 150 rooms, glass rotundas, grand ballrooms, spiral staircases, and decorative details 'copied from the Temple of Erectheus at Athens', laid on enough glitter to impress even the generally unimpressible Charles Dickens when he visited in 1842. New Orleans, true to its nature, contributed two of the grandest establishments on earth, and stories to go with them. The St Louis and St Charles not only competed for customers; they were the headquarters of two distinct cultures in a city where the French still held their own against the Americans. Their St. Louis was claimed as 'the largest and handsomest hotel in the world', while an English visitor called the soirees in the St. Charles drawing rooms 'the very court of Queen Mab'. Within a few years of their building, both the St. Louis and St. Charles burned down, and both were immediately replaced. The other significant public meeting places, the taverns, were everyone's home away from home, excepting ladies with social pretensions. They came in all sizes and degrees, and when you were dry you would never have far to walk; a visitor to pre-Revolutionary New York wrote that every third building contained one. Tavern keepers had always been public men, and their establishments might be the accustomed hangout for a political club, a fire brigade, or a profession. For bigger crowds and special events, there were the public halls. Located all over town, but mostly in the center, these were the sites for private parties, concerts, dancing, and meetings of all kinds. Halls became an essential part of the new democracy, and every town had a good supply, built for political clubs, ethnic associations, travelling lecturers or simply as a business; some were big enough to hold state and even national political conventions.

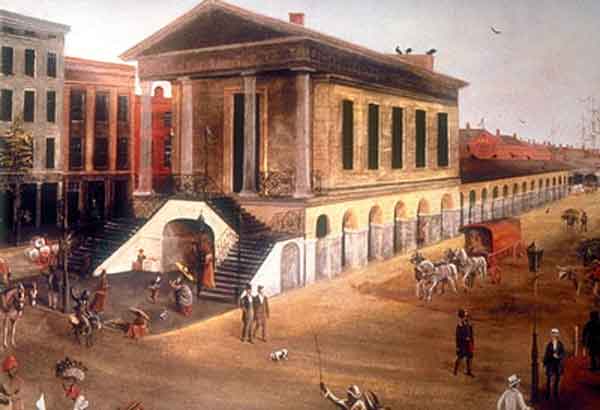

Charleston Market Hall in the 1850's, typical of the retail market buildings at the

center of an old market district. The elegant upper level probably held

city offices, following a building tradition that goes back to the

Middle Ages

Surprisingly close to the city's countinghouse, you'll find its larder. Though such housekeeping seems foreign to us now, in the walking city grocers, porters, butcher boys and fishwives walked the same streets as merchants and clerks. The classic form would be a square or widened street with a long, narrow market building in it: as once on Market Street in Philadelphia, Detroit's Cadillac Square, or Cincinnati's Fountain Square. Examples with the market still standing can be seen at Boston (Quincy Market), Charleston, New Orleans (French Market), Wheeling and dozens of other old towns. Not just a supermarket, this was the hub of a complex market district, wholesale and retail, with each of the surrounding streets specializing in certain trades and services. There might be an open lot or square for barrows, separate markets for fish, meats or vegetables, big warehouses, services for farmers, and always, plenty of taverns. A haymarket would also be required, though these needed so much space they were often pushed to the edge of the city centre (Detroit's old haymarket at Michigan and Trumbull later became Tiger Stadium; every year the groundskeepers would turn up a cobblestone or two in the outfield). Regional peculiarities were relatively few, but the first market of St Louis, following old French tradition, also housed the town hall and the jail. New York doesn't have a proper market today, largely because pressure from the merchants of the smaller markets—the city once had 62 of them—kept a central one from ever being established. Residential patterns showed a little more variety. In the walking city, everyone wanted to live near work, even the merchants, and rising land values subdivided the colonial founders' 'town lots' into smaller and smaller bits. At the same time, many towns laid out in large blocks, such as Washington or Philadelphia, developed the common practice of building alleys into them (as Ben Franklin did on his large Market Street property). These back streets were the homes of the poor; a noticeable residential hierarchy without segregation by neighborhood. In New York, instead of back streets there were' back houses', filling in the rear of the city's long lots. In the north, urban living generally meant row houses, whether single-family or divided up into flats-or 'tenements', as they came to be known. At first, individual buildings of differing styles would be built one at a time, to the limits of the lot width. From the late 18th century on, they were increasingly constructed in terraces- following pattern books from Britain, until America started creating its own. They ranged from the august bow-fronts of the Boston elite to the utterly plain, gabled two-window models built by the dozen for the mechanics of Baltimore, NewYork and Philadelphia. Row-house uniformity was condemned by aristocrats and aesthetes; to others it symbolized American egalitarianism-'a pleasing uniformity of decent competence', as Hector St. Jean Crevecoeur described the row houses of Camden in Letters From an American Farmer. But as early as the 1810's there were merchants in New York wealthy and worldly enough to build terraces as fancy as those of Belgravia or Mayfair, tarted up with colonnades and marble veneer. For a skyline, the early city offered its circlet of church steeples, and beyond that the masts of ships above the rooftops of the business blocks. New York's Trinity Church, now looking so gloomy and small in the canyons of Wall Street, stood proud for decades as the tallest landmark in the city. By the Civil War many big towns had a ready promenade to take in the view-before there were parks, the city would often landscape the grounds of its reservoir, built up on a terrace at the highest elevation available, and it was easy to pave a path around the water for Sunday strolls. Only gradually did cities bother creating public monuments, and when they did, the motives were less from ideals of city beautification than patriotism—and occasionally real estate schemes. The first appeared in Baltimore, the brash boomtown of the early republic; the 1815 Battle Monument commemorated the city's single-handed victory over the British Empire only three years earlier, the fight that inspired' The Star Spangled Banner'. Baltimore followed this with a much more impressive one, the Washington Monument on what is now Mount Vernon Place; like many city projects of this time, this one was financed by a lottery (and it soon turned into the core of a lot promotion). Other cities followed. Boston's Bunker Hill Monument started to rise in 1832; the granite blocks for it came in from Quincy on America's first steam railroad. Baltimore, a pioneer in American sloganeering as well as city-building, kept faith with its self-coined monicker 'Monumental City' through a number of other projects, notably Benjamin Latrobe's lovely Cathedral of the Assumption, and an elaborate Exchange dominating the port. Baltimore nearly became the first city to attempt a really ambitious aesthetic improvement. Flooding along the stream called Jones Falls, in the heart of the city, was a chronic problem. Robert Mills, architect of the Washington Monument, proposed a scheme in 1817 for widening it, with low wharves to contain flooding, and a promenade along the bank to increase property values. Mills' vision, which might have left Jones Falls looking something like the Seine or the Tiber, proved slightly too rich for both the pocketbook and the imagination of the day, and the city finally settled on a cheaper plan by his rival Latrobe, tunnelling a flood relief channel under a hill. Until urban opulence grew able to fund grand schemes, the one cheap and universal amenity in the American town was the humble shade tree. From contemporary accounts, it seems that the habit of lining streets with fine trees, usually native elms and oaks, goes back to the beginnings, to the 17th century, and that it was considered so natural that it occasioned little notice, beyond admiration from visiting Europeans. St Louis's first elected mayor, William Carr Lane, won in 1823 on a platform of improved wharves, a school and hospital, and most importantly, trees, not only for improving the city's appearance but to 'restore the vitiated atmosphere'. As the city grew more complex and articulated, people coined new phrases to describe its parts. 'Down town' and 'up town' were first heard in New York in the 1830's, as the built area advanced up the narrow island. Those names were already common in New Orleans, where 'downtown' (down river, really) was the French Vieux Carré, while the 'uptown' faubourgs east of it made up the new American district. Only gradually in the course of the century did 'downtown' come to mean any city's central business district. And as their increasingly developed economies spawned class differences, these too came to be epitomized in the geography. Only the railroad was lacking for the 'wrong side of the tracks' to magically materialize. In cities where the poorest of the poor were not confined to alleys, their districts tended to be small and intimate, and set in central locations; New York's notorious Five Points, the most overcrowded and dangerous slum young America knew, was four blocks long, and it began just behind City Hall. Despite the presence of the city jail on its edge (the famous Egyptian revival building called the Tombs) this was New York's red light district, and also for a while the first police 'no go' zone in. Over the decades, places like this would be gradually taken over for commercial uses, while their populations, often predominantly Irish, got pushed out to less desirable real estate near the industry and freight yards. |

|

|