Serial Vision: A Walk Around the HagueGordon Cullen's concept of serial vision, one of the key elements of urban design, is something may people find difficult. When even most architects understand only the static sort of building composition common to Classical or Modernist work, something digestible at a glance, understanding informal design with its dynamic way of grouping buildings requires a kind of revolution in seeing. It's worth the effort. I never bothered to record an example before (largely because I'm useless at photography). But recently we had a chance to visit the Netherlands, and I thought I would look for one there to illustrate my point. Irregular street plans bring serial vision into being, and the Dutch have got plenty of those. I was fortunate to come across a fine example in the Hague. Here's how I found it.

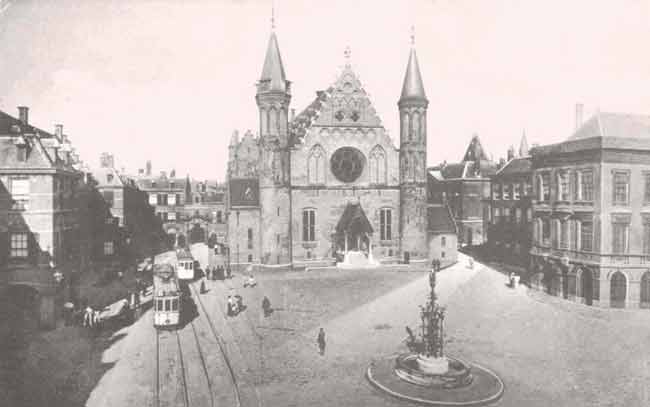

s'Gravenhage, to give it its proper name (it means 'the count's hedge') is a right peculiar old town. The Dutch like to call it 'biggest village in Europe', since for almost 600 years after its medieval foundation its people never bothered to incorporate it as a city. Before I arrived, I had only this rather poor map to look at, drawn by a cartographer of a modern sensibility who might have done a much better job at capturing the important pathways of this city. We shouldn't be too hard on the cartographer, really, since the Hague has given itself a rather poor street plan too. We're looking at something that offers very little useful information. Sure, it might help you find an address, but the map gives very few clues about the form of the city. It's hard to tell where the center is, or if the Hague even has one. Right, I thought, this is just the sort of town I'm looking for. In places that history has blessed with an inscrutable mess of a town plan, I have found, people are often more likely to try and correct the deficiency through urban design. What looks a muddle on paper just might make sense on the ground. We've been over this all-important difference between paper design and eye-on-the-street design in our discussion of Camillo Sitte. It is what we might call 'formal' and 'informal' design, or perhaps 'medieval' and 'Renaissance'. From Sitte too, we have the key to informal design, expressed in the quality he called malerisch, or 'painterly'. Such design seeks to create a composition, in a subtle and sophisticated way, as a painter would. Unlike Sitte, who put the phenomenon down to the artistic skill of the medieval architects and the survival of techniques from antiquity, I suspect that informal design at times comes almost unconciously, to even the humblest patrons and builders. Once the habit is established in a city, it becomes part of the air everyone breathes. The city is small, intimate, tangible and knowable to all its people in three dimensions. Whoever builds, large or small, feels the sweet invitation to perfect the vision, not vandalize it. After a morning in the excellent gallery called the Mauritshuis, among the Vermeers and the Rembrandts, we spent a couple of hours walking around. Finding the centre turned out easy—at the Mauritshuis we were already in it.

And this is where I found a bit of serial vision. Let's backtrack a bit and capture it in its entirety. Imagine you've just arrived from the rail station, and you're looking for the center of town. The path becomes obvious when you notice a hint of tall gables and spires towards the west. You walk down Herenstraat, and find your path blocked by buildings at the opposite side of a large square, called simply the 'Plein'. You can bear left, for a street that carries on in the same direction, or right, where a distinctive gateway beckons. Being forced into choices is common in design pathways like this, and often enough, as in this case, you'll find that both paths eventually rejoin. The right-hand path passes the Mauritshuis, from there, we take the little gateway...

And find ourselves in this lovely and spacious courtyard...

Once we pass through the far gate, we're in a

square called the 'Outer Court', the Buitenhof, and once

again we have to guess where to go next.

As we continue towards it, we see that this clue did not mislead us. Here, the pathway is emphasized by the corner turret of a commercial building, and a pretty iron and glass pavilion that now serves as a clothing store.

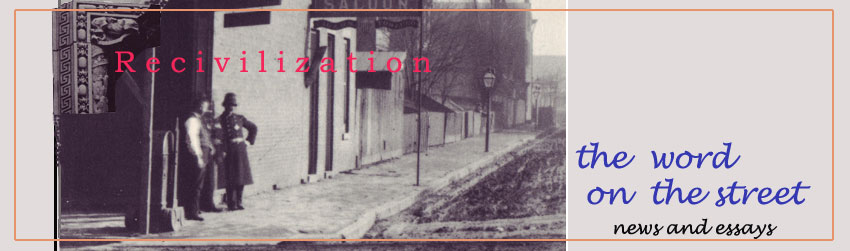

Round or sharply angled forms tell the eye that traffic is being diverted or divided. And here as before, the path bifurcates, both choices soon returning us to the same point, the climax of the trip. As we reach the pavilion, that big church looming over it seemed to promise that we were indeed nearing the center of this town, and in fact, we're here.

This is the Hague's main church, the Groote

Kerk. Only a small part of the long south wall is visible here, but

perhaps enough to give an idea of how its 14th-century architect

treated it, forming its gables and windows into a simple but elegant

backdrop for what at the time was a busy marketplace.

That's all the exploring we'll do for

now. Time for a café and a beer. But we depart noticing that,

like any good node in a town of informal design, this church square

points out some possibilities for further exploration. This is

Torenstraat, which leads off from the front of the Groote Kerk to the

Royal Palace. The low, curved

building in the center of the view seems to draw the eye onward

(somehow it is much more conspicuous in real life than in a photo).

It's only a parking garage, built in the 30's, but it shows

that even in fairly recent times, an architect could still

keep some notion of the old way of building.

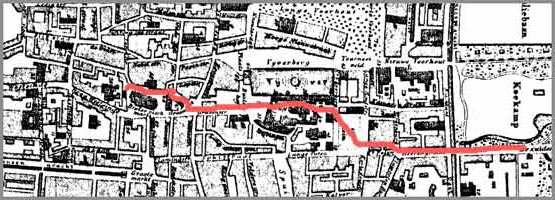

Here's the path we have just followed,

superimposed on an 18th century town plan. We learned, after looking

around a little more, that this is indeed the main pathway through the

city center—but you'll never find it on any map! Anybody who sends me another such documentation of

good serial vision, with illustrations, gets a duck dinner in southwest

France whenever you're in the neighborhood. |

|