163 recivilizing the roads

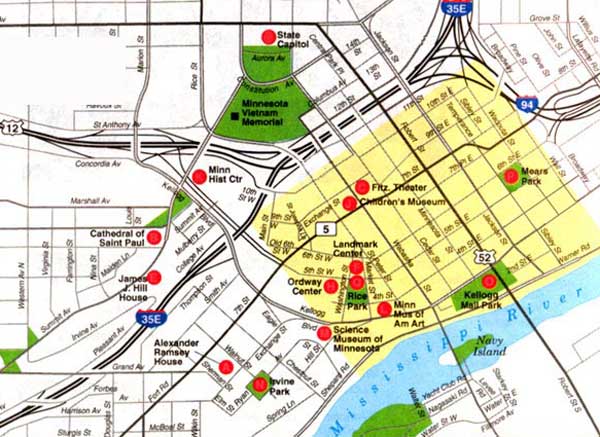

A central tenet of highway planning in

the bad old days was the 'inner-belt' or 'downtown connector'. It

usually took the form of a ring or partial ring around downtown, built

as closely as possible, like a noose, as can be seen in this map of

downtown St.Paul, Minnesota. Nothing since the coming of the railroads

proved more destructive to city centers. Now that most centers can no

longer play such as strong role as metropolitan business and retail

districts, we know now that their future—and that of the city

as a whole-depends on centers expanding their size and scope. The

presence of contiguous residential districts is crucial.

That consideration alone trumps all the abstractions of highway engineering theory. In most cases, the inner belts must go. It will be excruciatingly difficult, screamingly expensive, and it will require decades-a lesson, and a convincing argument for not doing stupid things in the first place. The construction of the urban Interstates was not only an epochal disaster for American cities—it was also one of the greatest missed opportunities. Highway construction according to the standards set by highway engineers meant that every goal of real city-building—utility, coherence, beauty, amenity—was sacrificed to the single consideration of moving traffic as speedily as possible. We all know the macabre joke in the result. As the rush hour jam-ups on our downtown freeway exits demonstrate daily, they couldn't even achieve the one thing they promised. It's time to start discussing ways to civilize the highway, to reintegrate it into the fabric of cities. We're talking revolution; the half-hearted efforts the more progressive cities have already undertaken will not suffice. The job will require federal legislation, to effectuate the renunciation of federal control over standards, design and funding. And Washington might be expected to kick in a little extra to resolve problems it created in the first place. No level of government ever relinquishes a power willingly, especially not to a lower one. States and cities must be loud and unanimous in demanding it. Even under the present dispensation, dominated by Washington and its road lobbies, cities such as Portland, Oakland and San Francisco have already rid themselves of superfluous bits of freeway. Every other city should start looking to isolate the worst parts of their own systems, and usually these will be the 'inner belts' and connecting links around downtowns. The argument for their removal will follow the general principle that the people of Baltimore adopted in their successful anti-freeway fights of the 60's: cars may be brought in and out of the center, not rushed through it. In St. Paul, above, the center is strangled by highways, including the dreadful I-94 connector that isolates Cass Gilbert's wonderful state capitol and makes a wasteland of its surroundings. On the left side of the map, note Summit Avenue, the street where Scott Fitzgerald grew up and still one of the most beautiful residential avenues in America. The stretch where Summit meets the city center should be one of the key areas of St. Paul. Once it was, but you can see easily enough on the map what the highwaymen did to it. Across the Mississippi, Minneapolis might consider removing bits of I-94 and I-394, restoring the integrity of the once-gracious area around Loring Park, and giving downtown the thriving, contiguous residential neighborhood it needs to function as a real city center. Similarly, taming the end of I-35 West with its jungle of ramps and overpasses would reconnect the center with the University of Minnesota's West Bank campus. Not all downtown freeways can be easily trifled with. In Chicago and Los Angeles, and in cities where no 'beltway' or other three-digit Interstate carries long-distance traffic around the edges, the engineering problem is monumental. In every case, the job is a formidable one. If you can't get rid of the beast, you might bury it, as Boston has done with its 'Big Dig', removing the hideous slash through the historic center made by the Central Artery in the 50's. That, the last time we looked, was costing Boston and the federal taxpayer $12 billion. If you can'teliminate it, or turn it into a parkway, or bury it just yet, try covering strategic parts of it, as Seattle has done, covering part of I-5 with a (somewhat peculiarly) landscaped park to connect downtown to the new convention center. Or Columbus, Ohio, which has come up with the rather sparkling idea of building on 'air rights' where High Street, the main drag, crosses a freeway just north of downtown. Freeways are intimidating, almost impenetrable barriers to people on the street, even where pedestrian bridges or tunnels are present. Columbus's plan makes the horror at least partially disappear. Freeway caps are rapidly becoming a hot idea among planners. Look for (or make) a proposal in your town soon. Air rights in general—the idea of building over roads or railroad tracks or whatever—is a woefully underutilized strategy. It's sometimes a difficult task for engineers (and lawyers), and lazy cities don't always consider it. But covering up strategic waste spaces and connecting urban tissue should be part of every city's strategy. California builds elevated freeways while other states dig trenches for them. Why shouldn't elevated freeways cover the routes of rail tracks wherever practicable? Outside downtowns, some-lightly-used freeways can be converted into boulevards or parkways, as Cleveland plans to do with its earliest controlled-access road, the West Shoreway. Here, lowering speeds and reintegrating the road with the surrounding street pattern will create a fine parkway, while it opens new land for development and improves access to the lakefront and Edgewater Park. Could any reasonable soul say that an average 40 mph is too slow to pass though a town? if the trip into a city is five miles, driving at 40 instead of 60 costs you a whole five minutes. Speed makes a meaningful difference in long-distance journeys, not cross-town commutes. Reducing speeds, incidentally, also increases highway capacity, since with a reasonable safety distance between cars, as we are taught to drive, the fast car occupies much more space on a roadway. According to the Transportation Research Board's Highway Capacity Manual, the optimum speed for capacity is 30mph. Reforming road systems means not only freeways, but the entire urban system. It offers a great opportunity for every town to haul out the plans of Olmsted and George Kessler and H. W. S. Cleveland and the rest, from over a century ago, and learn to apply sound design to the job of recivilizing the city. It is a challenge to the traffic engineers; if they aren't up to the task the architects or landscape designers will have to take over. The narrowing of streets has been a popular topic in recent years. Plain common sense—because narrower residential streets are safer, cheaper and waste less land-has brought their adoption in such unlikely places as Orange County, where the old mandated 36-ft width is becoming a cosier 24ft. The old street standards had been set by the National Institute of Transportation Engineers in the 60's. They were supposed to promote safety, but studies have shown they produce the reverse effect, since they encourage people to drive faster. Converting a four-lane residential road to three, with the center one for left turns, has proved a successful means of taming traffic in residential areas. Among the road narrowing projects inspired by New Urbanist designers, there is the Miracle Mile of Coral Gables, and the business district of Santa Monica, California. Santa Monica's council has voted to expand sidewalks and create bus lanes on Broadway and Santa Monica Boulevard, hoping to build on the great success of its pedestrian Third Street Promenade. Along these lines, there's the trend for 'traffic calming', slowing down cars in residential areas for safety. This has already become widespread in Europe. Some of its elements are lower speed limits, speed bumps. or 'humps' (the British call them 'sleeping policemen'), 'in-and-outs' (obstacles that slow you down by bending the path of the roadway), ' urban pavements' (traditional brick, or special intersection paving) and traffic circles. They have some history in America too. Traffic circles, for example, have long been used in some west coast cities: Seattle, Portland, Berkeley. Seattle has some 700 small ones on residential streetcorners, which are credited with cutting accidents by 94% over the simple intersections they replaced. Now they're springing up everywhere in California, where chronic congestion is forcing more and more cars off the main routes and onto residential streets. European countries in recent years they have been leaning towards a more systematic approach to them. 'Home zones', an idea that began in the Netherlands, is currently being tested in neighborhoods around Britain. It means a complete package for residential areas, including signage, lower speed limits-preferably to 10 mph-traffic calming devices, and pedestrianizing some streets in high density areas. There's a marked difference between a Europe that is working steadily to reclaim its streets and public spaces, and an America still consumed by the hope of zipping through town as fast as possible. A suburban London taxi man told me he guessed he rattled over some three hundred speed bumps every day-'but if it saves a few kids it's fine with me.' Recently, in two Ohio towns, newly-installed speed bumps were removed at the insistence of fire chiefs. Traffic calming with a wider purpose is a specialty of Oscar Newman, who has adapted his insights of 'defensible space', pioneered in St. Louis's Pruitt-Igoe project, to residential neighborhoods. He directed a project in a troubled neighborhood of Dayton called Five Oaks, plagued with drugs and crime, and the disarray of distrustful neighbors in a changing area. Newman's idea was to create 'mini-neighborhoods', in effect suburban-style cul-de-sacs where pedestrians pass freely but cars are blocked by barriers-attractive, permanent street redesign, not just a row of orange barrels. Coupled with extra police attention and code enforcement it effected a remarkable turnaround, changing perceptions, increasing property values, and bringing neighbors a little closer together. |

|

|